Ever since Sir Walter Scott invented historical fiction with his novel Waverly (1814), there have been many kinds and definitions of the form.

Ever since Sir Walter Scott invented historical fiction with his novel Waverly (1814), there have been many kinds and definitions of the form.

One of the questions that comes up repeatedly is historical accuracy. It is a complex question and usually has an equally complex answer. One can try to be accurate, but it is almost impossible to be completely accurate.

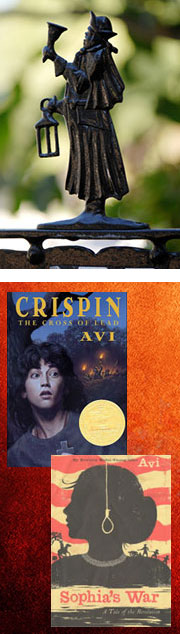

Start with language. My Crispin, takes place in 14th Century England, at a time when Middle English was spoken. Never mind that I cannot write Middle English, my readers could not read it. Therefore, I tried to give the prose a poetic beat, to approximate a Chaucerian voice. Different, but readable.

In Sophia’s War, in which 18th century colonial English is spoken, I tried to employ word usage of that day, to suggest a voice from that time. Thus “Shay-brained,” for silly, or “hurly-burly” for commotion. In addition, it was useful to be aware that colonial English could be different from, say, London English of the time. Maybe my readers will not catch that, but it is meaningful to me as a writer.

Sometimes I’ve been taken to task for putting too much religion in my medieval novels, or, for example, in a novel set in the 1950’s for allowing my adult characters to smoke too many cigarettes. Yet, as far as I am concerned, it is the way things were and it helps tell the story in a vivid historical context

My approach is to try to differentiate the historical time from the present time by showing how characters thought in such and such a time, even as I reveal a physical world that is not the contemporary world. That said, emotions, motivation, and personality must be recognizable to my readers today.

In short, one wants to avoid potheration (18th century English for confusion) while making the book upstirring (18th century English for stimulating).