Consider these two items:

- I have been asked to do (and accepted) some lecturing at UCLA on the subject of historical fiction.

- Last week, when talking to a fifth grade class, a boy asked me, “What was it like in the Twentieth Century? Did it have any influence on your writing?”

Let us consider the first item. Most literary historians consider Walter Scott’s novel, Waverly, the beginnings of English language historical fiction. Because he set his story sixty-five years prior to his writing, there is a canonical notion that sixty-five years delineates “contemporary fiction” from “historical fiction.” Debatable on all points, but these are useful markers. I have always—after many tries—found Waverly unreadable, but I like it that the main railway station in Edinburgh is named after the novel, one of the few historical fiction facts I can mention in my lectures. The point is I am going to be hard pressed to talk about my writing of historical fiction in an academic context. I do not know much about it, except that I do it. Yes, I read a lot of history. I know how—being a former research librarian—to do research, but in the main my approach to writing historical fiction is … I find a way to tell a good story.

Let us consider the first item. Most literary historians consider Walter Scott’s novel, Waverly, the beginnings of English language historical fiction. Because he set his story sixty-five years prior to his writing, there is a canonical notion that sixty-five years delineates “contemporary fiction” from “historical fiction.” Debatable on all points, but these are useful markers. I have always—after many tries—found Waverly unreadable, but I like it that the main railway station in Edinburgh is named after the novel, one of the few historical fiction facts I can mention in my lectures. The point is I am going to be hard pressed to talk about my writing of historical fiction in an academic context. I do not know much about it, except that I do it. Yes, I read a lot of history. I know how—being a former research librarian—to do research, but in the main my approach to writing historical fiction is … I find a way to tell a good story.

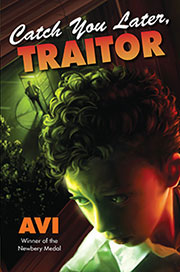

And indeed my forthcoming novel, Catch You Later, Traitor, is based in large part on my memories of that time. It takes place sixty-four years ago. Does that make it historical fiction or contemporary fiction?

And indeed my forthcoming novel, Catch You Later, Traitor, is based in large part on my memories of that time. It takes place sixty-four years ago. Does that make it historical fiction or contemporary fiction?

Which brings me to the second item cited above: My new novel will certainly be historical fiction for that young reader, but not for my contemporaries who lived through the same period. These days, most people know history to the extent that they have lived it. We are not a historically-minded society. Not only do most of us know little of history, we have short memories.

As a result, I have a tendency to be dubious about labeling various genres of fiction. I am reminded of something one of my sons said to me when he was working as a musician. “Dad, there are only two kinds of music. Good and bad.”

Concerning writing, that works for me.

3 thoughts on “Are there only two kinds of fiction?”

When I taught children’s literature, historical fiction was always a tricky genre to discuss. I worked with preservice teachers and would often use the events of 9/11 to “push” their idea of history. They remember that day as “contemporary” and the elementary students that they will be teaching will know it only as history.

Because of the way that the course was designed (and they ways that they will be asked to “use” literature in classrooms), it was necessary for us to have some sort of common understanding of children’s literature. Students often wanted for some sort of definitive “cut off” — e.g. if it’s more than 20 years old than it is historical.

I eventually came to push them away from that and consider more deeply what and how the “historical’ aspects of a book functioned in the story. If it takes place in 1965, what is important about that year that helps us understand the characters or events? If the characters in a book were actual people in history, how do they help us understand the other characters? The plot? etc.

The more I think about it and as I write this, the more I think that the notion of history as part of story is more about how it functions as a literary element or device and less about defining a genre.

We were just discussing this in my CL class today. I’m going to bring Avi’s blog post and your thoughts, Kristin, to my students on Thursday to add to our conversation. Thanks for (virtually) coming to class!

I completely agree with you.