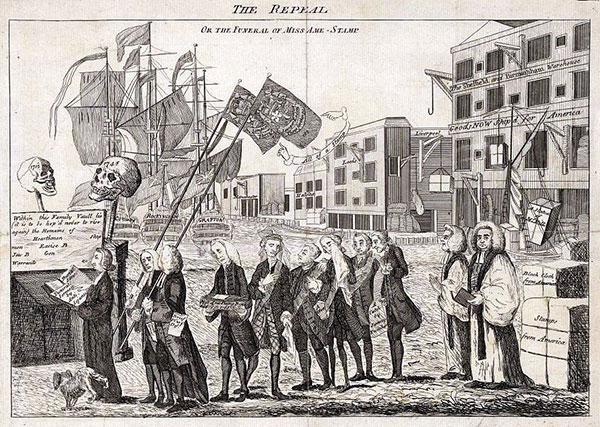

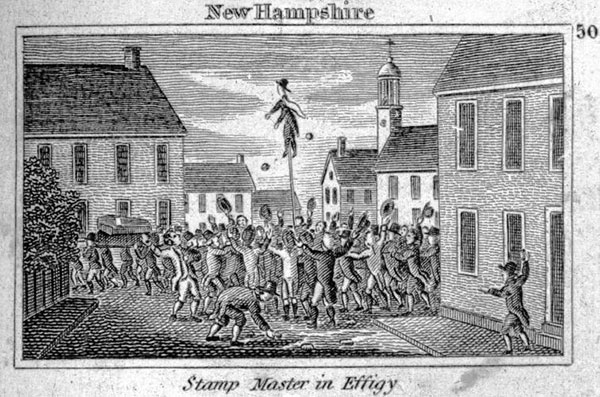

In the Thirteen American colonies, ten years prior to the Revolution, there was what was known as the Stamp Act crisis, which, in Boston in particular, brought forth that iconic cry.

By representation it was meant there was no American seated in the British Parliament.

“But,” according to historian Brian Deming, “the idea never gained traction in Britain.” As one British critic of the time wrote: “Shall we live to see the spawn of our Transports occupy the highest seats in our Commonwealth? Degenerate Britons! How can ye entertain the humiliating thought!”

The key word here is “Transport.” It references the many thousands of transported felons who had been shipped to the colonies for forced labor by way of punishment in the 18th Century.

During the 18th Century, England became a center of great wealth and mass poverty. Crime against property became commonplace. In reaction, the British government enacted harsh laws to punish minor and major offenders—a collection of laws that collectively came to be known as “The Bloody Codes.” One major punishment was transportation, by which children, women, and men were sent to British American colonies and sold into forced labor.

At the time of the Revolution there was a colonial population of two million. Some fifty thousand were (or had been) these transported felons. (Hence the quote cited above.) It had become a business. It was 1619 when the first Africans were brought to America as slaves. There was a time when enslaved whites and blacks labored together.

This is the context in which my newly published The End of the World and Beyond takes place. In book one (of this two part series) The Unexpected Life of Oliver Cromwell Pitts, my eponymous hero becomes entangled in crime and British Law. The sequel tells the story of what happened to Oliver when he was is transported to Maryland and sold.

This is the context in which my newly published The End of the World and Beyond takes place. In book one (of this two part series) The Unexpected Life of Oliver Cromwell Pitts, my eponymous hero becomes entangled in crime and British Law. The sequel tells the story of what happened to Oliver when he was is transported to Maryland and sold.

Booklist reviewed the book thus: “Though darker than its predecessor, this sequel is equally fine. The plotting is altogether laudable, the setting beautifully realized, and the characters highly empathetic. Especially good is the voice Avi has conjured for Oliver, just antique enough to evoke eighteenth century diction and syntax. One thing is certain: it may be the end of the world but there is no end to the pleasure Avi’s latest evokes.”

4 thoughts on ““No Taxation Without Representation””

Been a fan ever since I read Crispin. Wish I could have met you when you came to Tucson.

My students and I love your books. Last year we turned Sophia’s War into a play. The students performed it for their parents. They even went out and bought costumes. It was a wonderful time for all! Thank you for your inspiration!

Sorry I wasn’t there.

Bravo, once again. ‘…just antique enough to evoke eighteenth century diction and syntax” –You should write a post about just this. How to write dialogue (or first person narration) for another time or another place that is easy for a young contemporary reader but doesn’t sounds contemporary.