After a brief stint at Antioch College, I went to the University of Wisconsin (Madison). There I had a double major, theatre and history. I was a B- student. I avoided every English class I could.

(If you haven’t yet read Part One of this essay, click here.)

When in college I asked a much older writer to read some of my writing.

His memorable response: “Avi, it takes a heap of manure to make a flower grow.”

When I was a senior, there was a student playwriting contest. I entered it. I did not win, but I did receive a comment from one of the judges: “The writer of this play is clearly not a native English speaker. But he has made considerable progress and should be encouraged in his studies.”

The next year I entered the contest again and won. The script was published in the student literary magazine, my first published work.

I continued writing plays, and while there were some successes (an off-off Broadway showcase production) and a director who did want to produce one of my plays in London, nothing much came of it. But along the way I acquired a good agent, which propelled me into the world of the professional writer,

When writing unproduced plays became too much of a frustration, another older writer friend—in retrospect what we would call a mentor—urged me to switch to writing novels.

I tried that. There was some interest, but not much more. My agent did report that one editor, upon reading one of my manuscripts, bestowed upon me “The F. Scott Fitzgerald Bad Spellers Award of the Year.”

By that time, I had children of my own. One of them, Shaun, liked to climb upon my lap before bedtime and ask for a story. He would tell me the subject. “Rain.” “A garbage truck.”

I would invent a story on the spot.

At that time, I liked to amuse myself by doodling funny line drawings. Some of them were even published as humorous greeting cards. A writer friend wrote a book for children and went to an editor with my illustrations. Her book was rejected, but the editor called me and asked me to illustrate another children’s book. “I’m a writer, not an artist,” I said. Her reply: “Then write a book and illustrate it.”

I wrote out those stories I had invented for my son and did some illustrations. When the editor saw the work, she said, “You are right. You are not an illustrator, but I like the stories. I’d like to publish it.”

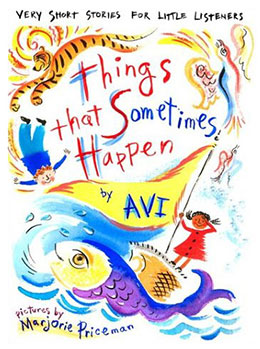

Shortly after, that editor left publishing, so the stories were circulated elsewhere. After the normal sequence of rejection, Doubleday decided to publish the book. Things that Sometimes Happen, was published in in 1970, my first book for kids.

When first published, the book received poor reviews, and went nowhere.

(In 2002 it was revised, republished and got good reviews. It’s still in print.)

But the writing and publishing of that book brought me into the world of children’s books, and I never left it. I’ve been publishing now for more than fifty years.

It was only in my mid-forties, when visiting a school, and showing my writing process—that is, my working manuscripts—that a reading teacher said to me, “Are you aware that you have dysgraphia?”

Here is a definition: “Dysgraphia) refers to (a) the language-based difficulties involved in constructing meaningful and effectively structured expressive writing and (b) ongoing weaknesses in spelling and punctuation that affects a student’s capacity to express their ideas with clarity.”

That was the something my parents discovered about me so long ago.

When I learned this, I went to my father—my mother had passed away—and asked him if he had known I had dysgraphia. “Oh sure,” he said. “Why did you never tell me?” “That was your mother’s decision.”

That knowledge did a few things: It was a revelation. I greatly eased my frustration. It took away my self-anger.

In short, having dysgraphia didn’t really matter. I was writing and publishing. More to the point, I had found a writing process—computer, spell-checker, endless re-writing—that mitigated my problems with the way my mind worked. Though these days it is still there, it’s nothing more than a nuisance.

That said, in my opinion, the person who invented the spell checker should have won the Nobel Prize.

And I’m still writing.

5 thoughts on “Becoming a Writer, Part Two”

I have questions and am very interested in your experiences and dysgraphia. When we were in HS we had readers who checked for grammar/punctuation/spelling and then the teacher gave us two grades:one for content, one for mechanics. When you wrote as child did your spelling make your sentences unreadable or was there more to it. IE leaving out words. Of course the laboriousness of handwriting for young kids and for those with dysgraphia makes it an unpleasant experience. Could you express yourself well when telling a story back then? It seems taking dictation would help. I find it intriguing that your current status as a really revered and prolific and beloved writer of many styles of books, could have had such a tricky start. I mean have you seen the drivel that competent spellers write as children. Form is great, content not so much. i would love to hear more on this topic about your writing. I am assuming you have no examples of your chlldhood writing.

As always, thank you for sharing and especially for sharing such a personal story. You are a definite role model for our youth who struggle with written expression and reading. Your openness about your journey is inspirational.

Avi, I have enjoyed reading your blog for more than several years now. And truthfully, I have saved most of your posts in a file of my own labeled ” for Writing.” With this part two post on becoming a writer I especially like the inclusion of your early teachers’ comments. I’m so glad you kept on writing and didn“t give up!!

Thank you for sharing your journey.

Thank you for sharing. Your story is very inspirational.