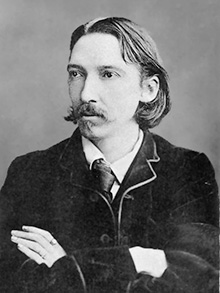

If I had to pick one book—from my early reading—the one that most influenced the way I think about books and the writing of books, it would be Treasure Island, written by Robert Louis Stevenson. Though he had already established himself as a gifted writer of short stories and essays, Treasure Island, astonishingly, was his first novel.

He would write, “On a chill September morning, by the cheek of a brisk fire, and the rain drumming on the window, I began The Sea Cook, for that was the original title. I have begun (and finished) a number of other books. But I cannot remember having sat down to one of them with more complacency.”

Complacent! Beyond all else, this is a wonderfully throbbing novel, with more energy and life on every page than some books have with 300 pages.

Building on his familiarity with earlier nineteenth-century writers of adventure stories — Kingston, Ballantyne, Marryat, and Cooper — Stevenson meant this as a story for boys and wrote Treasure Island in particular for his stepson Lloyd Osbourne.

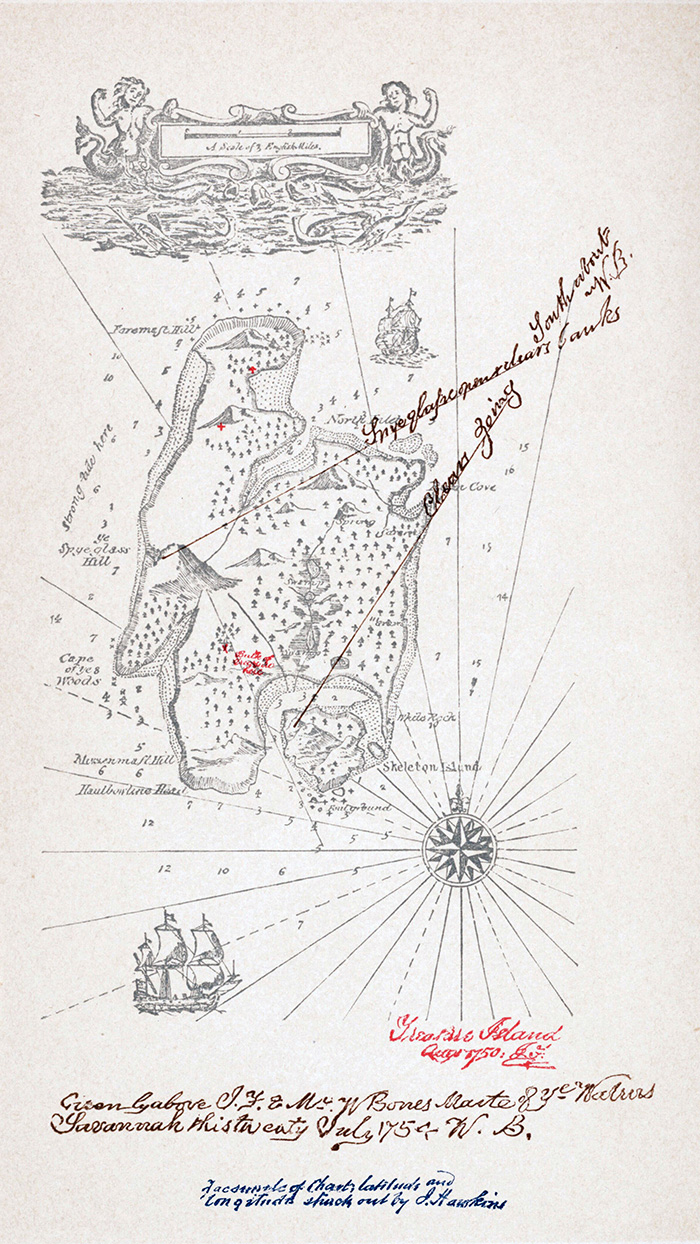

Famously, the idea of the book began with a drawing of a map — a map of what would be the island with the treasure [see the end of this article]. Any edition of the book should have that map replicated. There have been numerous attempts to locate the “real,” island, and has been claimed from Puerto Rico to California to Scotland. I have little doubt that it is fictitious.

As for the tale itself, there is extraordinary intensity in the telling, for the most part in the voice of young Jim Hawkins. That, I have little doubt, is part of its attraction for youthful readers.

And the characters that people the story, oh the characters! Beyond all else, there is Long John Silver, the leader of the pirates, who swings from soothing kindness to murderous betrayer with nary a slip of light between. This oscillation, in fact, reminds me of another of Stevenson’s great works, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, written a few years later.

It is Silver, one-legged, peg-legged Silver (and his constant companion, the parrot Captain Flint) who pushes the story forward even as he pushes his money-mad crew forward. Silver is filled with such life, such charm, such rich language that I think we are relieved (as I suspect Stevenson was) that at the end of the story he escapes to live out his (fictional) life.

But there is also Ben Gunn (and his deep love of cheese), Old Pew with his blindness, and Billy Bones with his songs. I can talk about them as if they were old friends.

The good guys, the squire and the doctor, are not nearly as interesting characters as the bad guys. Truth be told they have no more rightful claim to the treasure than the pirates.

Indeed the story is full of moral ambiguity.

It is also, to be sure, a violent story with much death and mayhem. Only five of the original crew return to England. That said, all the fighting and murders have an element of fantasy about them, as if to say, if you are going to tell a tale of pirates you just have to do this — but don’t worry — it’s just a story.

And if you can get hold of the book with the 1911 full-color illustrations by N.C. Wyeth, they match the genius of the text. For many years I had a copy of Wyeth’s image of Blind Pew over my writing desk, a reminder to work hard and find my own blind way as I wrote.

As for Stevenson, never a healthy person, he died very young, leaving behind a legacy of a wonderful person, much loved and admired.

Henry James, the great English writer, who was his good friend, wrote this to Stevenson’s widow. “For myself, how shall I tell you how much power and shabbier the whole world seems [with Stevenson’s death]. He lighted up one whole side of the globe and was himself a whole province of one’s imagination.”

I can say as much for Treasure Island.