If you are learning about the Unites States of America, you are learning about the history of immigrants to North America. The first Europeans (Vikings) came to America in 1021, and the most recent immigrants came, well, today.

When a certain Lawrence Washington died (1654) in England in poverty, his son John Washington emigrated to the American colonies — and became the ancestor of George Washington.

On my father’s side, my grandfather came to NYC in 1891 or 1893. The record is unclear. On my mother’s side, the year of arrival was 1890. The family story is that my great grandmother (and her five children) passed through England on the way. Pausing amidst the great labyrinth of the Liverpool docks just before departing, Great Grandma (known as “Little Grandma” because of her five-foot size) left the children and went off (to find a bathroom?) only to come back to find Charles (my grandfather, aged two) missing. A frantic search ensued, and just as the ship was about to leave, he was rescued from an aimless walk.

I suspect that there are countless American family stories akin to that one, the journey to point of departure, the voyage itself, the arrival, and early years of tragedy and/or triumph.

In fact, my grandfather — the Charles cited above — became a social worker, whose particular focus was reuniting married couples who immigrated at different times. It was common for the husband to come first, and only gradually earn enough money to bring the family over, not always with happy results. (See Hester Street, the 1975 film.)

It is one of the curiosities of American history, that though its history is also a history of immigration, immigrants have always been deplored, resisted, and disparaged — even as they continued, and continue) to come.

Peter Stuyvesant, (1610–1672) the governor of the Dutch Colony of New Amsterdam, (which would become NYC) was rebuked by the Dutch government for his not wanting to allow Jewish immigrants to come into the colony. Today Stuyvesant lends his name to one of the most prestigious high schools in the city.

Our history of slavery is a history of forced immigration — two and a half million. We sometimes forget that the Statue of Liberty — referenced most often as a monument celebrating immigration — was erected to proclaim the end of American slavery — and forced immigration.

In the 18th century, England had widespread forced immigration of felons — by the many thousands — were sent to the colonies as a form of legal punishment.

Then there was the 19th century Know Nothing Party, which gained considerable importance just before the Civil War, in large measure because of its violent anti-Irish Catholic immigration agitation. A hundred years later there was considerable resistance in the country to the candidacy of John F. Kennedy for the same anti-Catholic bias.

The western railroads could not have been built without Chinese immigration, even as those people were deeply discriminated again.

Thus it goes.

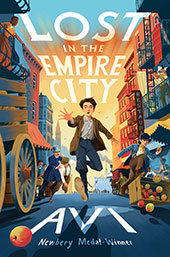

So if you are engaged in American history — as I am — to look at immigration in one form or another (voluntary or forced) it should come as no surprise that I’ve written about it a few times: Night Journeys, The End of the World and Beyond, City of Orphans, Beyond the Western Sea, and now Lost in the Empire City.

(The term “Empire City,” better known as New York City, is said to have had that nickname bestowed upon it by none other than George Washington. See above.)

Lost in the Empire City tells the story of Santo Alfonsi, who (in 1910) with his mother, brother and sister, follow their father to America, only for the boy to become separated when passing through Ellis Island. He lands in NYC, alone.

Lost in the Empire City tells the story of Santo Alfonsi, who (in 1910) with his mother, brother and sister, follow their father to America, only for the boy to become separated when passing through Ellis Island. He lands in NYC, alone.

Does he find his family? Were they sent back to Italy? What happens to his father? That’s all part of story. Though I like to think of the story as unique, it’s also probably a story which will resonate with many of my readers.

That’s one of the great bounties of fiction: stories we invent can remind us about what we often have forgotten.

3 thoughts on “Immigrants”

Insightful, honest, and a story I know well with my grandfather, Baptista and his wife Eda, who came through Ellis Island, settled in Montana (farmer) and had one child, my father Amerigo (Jim) Pagliasotti.

Love that name, Amerigo!

Glad to know your grandfather wasn’t lost in Liverpool. I think I prefer happy endings in stories.

I remember watching on TV reunions between siblings from north and south Korea who hadn’t met for the last thirty years or so. I felt a deep sense of pity for them.