One of the key tools a writer has is memory. In particular, it’s not unusual for those who write for young people to have engaging — and meaningful — memories of their own childhood. Such memories are often put to invaluable use not just in terms of story, but also in the details that provide authenticity to a youth narrative. When recalled, time, place, and objects can provide realistic grit to a fictional life. Such memories can capture not just places, but people, their relationships, and experiences.

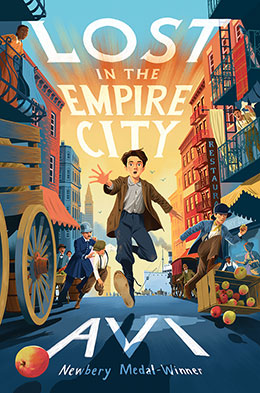

More recently, in my recently published Lost in the Empire City, early memories are embedded.

In the book much is made of the nineteenth and early twentieth century coal delivery shoots that were part of so many brownstone houses that still exist in NYC, including the one where I was raised. The memory is so strong that it was relatively easy for me to use it in the book.

Another:

During the post-war 1940’s my parents summered on an island — Shelter Island — in the middle of Peconic Bay, New York. It took a ferry to reach it. These ferries, with their load of fifteen or so cars, would, upon arrival at the island, smash into their piers of tar-blackened wooden pilings. Exciting for a kid. I remembered those moments so well I was able to use the same experience for my protagonist, Santo, when he arrived by ferry in NYC, from Ellis Island in 1911.

And the house he comes to live in is much like my own childhood NYC home, which was built in 1835.

Thus, memories of 1835, and the 1940’s touch my 2024 story set in 1911. Try stringing all those beads together!

But the author’s memory is also at play in a given book, so as to give depth, reality, and constancy to characters and plot lines. If a character walks with a limp on page one, she’ll need to have it on page two-thirty-six. Likewise, the character given to easy laughter early on must have a reason not to have it (or to have it) at the end of the book.

At the same time, readers look for change and growth in a character, but that possibility has to be built in. The point is: characters have memories.

And crucially, so do readers.