If you were writing a story set in 19th Century America I’m sure you would not have a character say, “I’ll check my inbox.” But it would not be absurd to have a contemporary character say, “When I do that, I intend to pull out all the stops.” And yet “pulling out the stops” actually refers to pulling out all the stops on an organ to produce its fullest sound.

Our language is full of what I call “fossil phrases,” terms we still use that are based on things or acts from the past.

Consider, “She’s a flash in the pan.” The “pan” is a kind of tool for looking for gold in a stream, and that “flash” may well be a bit of valuable gold. But probably not.

Or we say, “That person is still in the limelight,” when a limelight was a non-electric type of stage lighting once used in 19th- century theatres.

And thinking of light, some of us still “burn the midnight oil,” which means working late, but surely not using an oil lamp to keep us going.

If you refer to a person as “a loose cannon,” as in creating havoc, you are not thinking of a multi-ton cannon, which having slipped its holding ropes, is rolling around the pitching deck of a mid-ocean warship wrecking everything. But it’s a good metaphor for certain wild-acting presidents.

When you sit down and take on a hard task, you might say “I’m going to bite the bullet,” but I bet you are not thinking of going through a medical procedure so distressing you are given a lead musket ball to bite into so as to alleviate the awful pain. I once saw a basket of such chewed bullets in a Civil War museum, and just to see them made me wince.

If you are going to start something at “the drop of the hat,” my guess is that you are not involved in a foot race that began (as used to be the custom) when someone dropped his hat as a signal to begin the race.

“One for the road,” references a charming British tradition. When taking someone to the gallows to be hung, there was a brief pause at a tavern for a drink of something alcoholic so as to give the victim the courage to face death.

And of course, if you are going “full steam ahead,” it’s not likely you have brought your boiler to the point of producing steam so as to get your locomotive up to speed.

“Up to scratch,” seems to mean the scratch line in the dirt, where you are supposed to be standing when about to engage in a boxing match.

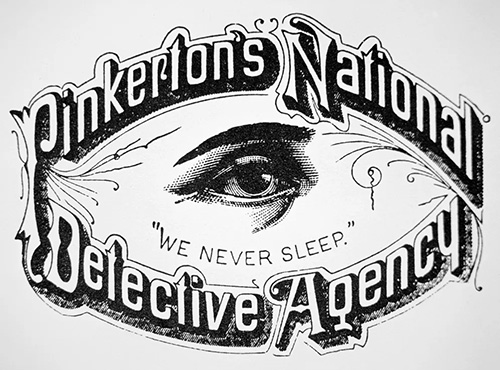

Or that “gumshoe,” you hired probably does not mean the detective is wearing shoes with early 20th century gum-rubber soles so as to render him stealthy. But if you refer to him as a “private eye,” that’s a reference to the 19th-century Pinkerton Detective Agency’s logo. They were hired to protect Abraham Lincoln on the way to his first inauguration.

When I was a boy and a game was about to start, I’d shout “I’ve got dibs” to proclaim my right to go first. I had no idea the term came from an 1800s game played with sheep knuckle bones called, well, “dibs.”

If you read “the riot act” to your child, I bet you are not thinking of the act of the 18th century British Parliament which authorized local authorities to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and order them to disperse or face punishment. Then again, if you are confronted by twelve unruly kids it might be a good idea.

In short, the language we use is very much like a linguistic museum.

Readers are encouraged to submit their own examples of Fossil Phrases.

6 thoughts on “Fossil Phrases”

I didn’t have a fossil phrase to submit, but did have a question-Is there any possibility of a sequel to “The Good Dog”?

Never say never. But not in my plans.

I love phrases with some history and growing and listening to my grandparents and also watching movies from the 30’s and 40’s and even watching Looney Tunes cartoons you hear all kinds of strange sayings. I equally love finding out the origins of these as well. History programs on tv often explain where phrases come from. I really enjoy knowing how these words and phrases ended up in our present day. I’m sure there are many that would be difficult to explain to people under the age of twenty!

I love finding out where idioms come from. When I taught, I had a book for children that explained the origins. My students were not happy when they found out how “raining cats and dogs” came about. According to the book (I don’t have the title and author handy), it came about when after a heavy rainstorm, there was a flood. After the storm, people looked outside and saw many dead dogs and cats and wondered how they got there. Though now, when I look it up, I find different possible origins.

- Back in a jiffy!

— I’ll give you a ring. Or, I’ll ring you later.

‑Sleep tight.

I just read this in the New York Times Flashback Quiz, “In ancient Syria (2400 BCE), the Kingdom of Elba sends livestock into the desert to symbolically carry away evil. They’re among the first known scapegoats.”