The other day while writing, I took something like fifteen minutes to find the right word for a sentence. It happens fairly often, for a variety of reasons: I’m trying to convey just the right nuanced emotion for the moment and I am a strong believer that every word contains some emotion, however slight. There’s also the question of sentence rhythm, the way it flows, and the way, therefore, a paragraph courses. I may choose a two syllable word, as opposed to one with three, or one. Then, too, I love words, find them fascinating, and love to play with them.

The other day while writing, I took something like fifteen minutes to find the right word for a sentence. It happens fairly often, for a variety of reasons: I’m trying to convey just the right nuanced emotion for the moment and I am a strong believer that every word contains some emotion, however slight. There’s also the question of sentence rhythm, the way it flows, and the way, therefore, a paragraph courses. I may choose a two syllable word, as opposed to one with three, or one. Then, too, I love words, find them fascinating, and love to play with them.

I am mindful, too, of my readers, and their ability to make sense of what I write. In that regard I have a self-imposed rule: Never put a unique or unfamiliar word in my opening paragraphs. I don’t want my reader to stop, and mutter, “This is too hard for me.”

As I pursue words I have an extraordinarily large choice. The English language has more than a million words, the largest vocabulary of all languages because it is an amalgam of different languages. Happily, English has been miserly about letting old words go, and generous about letting new words in.

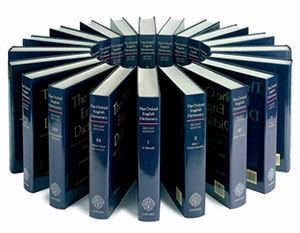

In this effort I have a silent partner (right in my computer), to which I often turn. Referenced as the OED, I mean the complete Oxford English Dictionary. It is a vast assemblage of words, all English words, definitions, and what I particularly love, an historical thesaurus. For someone who writes historical fiction, it is a crucial tool.

When writing historical fiction I hasten to say I do NOT check every word. But when I have a key word, I often look to see if the word was even used at the time of my story. Thus, a character of mine, in a current project, is asked to flirt with customers. But the word was not used at the time of my tale—1724. (Flirt enters the language in 1781.) To express the idea one wrote “to play the coquette.” (But historically, according to the OED, there have been fourteen (!) words used to express this. I can use them all.)

Thus, not “I became fully awake,” but, “I roused myself to full wake-fullness. Not, “The girl sat there sulking,” but “The girl sat there, pout-mouthed.”

This kind of working and thinking allows me to write something like this:

“No doubt it is unkind of me—the obligatory author of my autobiography—to leave myself—and you—in such a precarious predicament, possibly drowning and thus in danger of ending my life and my tale too hastily. But before I go forward, you need to learn something about the life I lived.”

As I see it, if you are not having fun with words, you’re not having fun writing.

3 thoughts on “Having fun with words”

Great truth in this one!

English Through the Ages by William Brohaugh (Writer’s Digest Books) is another resource. It categorizes words by use between1150 and 1990.

I once had a spirited discussion with my editor over the word “threadbare.” I love that sort of thing!