I worked at the Theatre Collection for nine years. After (I believe) four years, the Collection moved to Lincoln Center, to become part of the Performing Arts Library Center. There were three collections:, The Dance Collection, the Music Collection and the Theatre Collection. By then I was on the staff as a full-time librarian for the Theatre Collection.

I was put in charge of the Theatre Collection’s actual move to Lincoln Center. Aside from the basic book collection, and its archives, we were to bring in the previously stored collection (in un-catalogued and unsorted cardboard boxes) which had been—over the years—stashed in the library’s warehouse. I was told that it would take the movers a half day to move this collection to our new quarters.

It took two weeks.

What’s more, no one knew what was in these boxes, these hundreds of boxes.

As these boxes arrived, endlessly arrived, I began to open them. I found play manuscripts by Oscar Wilde, James Barrie, Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw … and more. Where did they come from? No one knew. How I found where they came from is an entirely different tale.

I continued to work in the Collection. I also became a theatre book reviewer for School Library Journal.

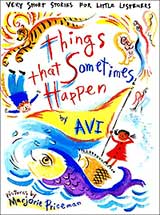

But things changed. I now had two sons, and was not happy about the prospects of available public schools. Also, my wife, who had been a dancer, stopped dancing, and changed her profession. I had also switched my writing focus from theatre to children’s literature. Indeed, I had sold my first children’s book, Things That Sometimes Happen.

But things changed. I now had two sons, and was not happy about the prospects of available public schools. Also, my wife, who had been a dancer, stopped dancing, and changed her profession. I had also switched my writing focus from theatre to children’s literature. Indeed, I had sold my first children’s book, Things That Sometimes Happen.

I tried to change my position in the New York Public Library to that of a children’s librarian. I was told that could not be done. “We don’t hire men as children’s librarians.”

![The library at Trenton State College [Wikimedia Commons]](/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ph_tcnj_library.jpg.jpg) I learned of an open position for Readers Advisor and Reference Librarian in New Jersey at Trenton State College [it became The College of New Jersey in 1996]. I applied and was offered the position. Though a relatively small college, it had a very large library, with a good, engaged staff, and a director who wanted a fine academic collection. One of the job’s attractions was that it was a faculty position, with a faculty schedule, which is to say: summers off. I’d be able to write.

I learned of an open position for Readers Advisor and Reference Librarian in New Jersey at Trenton State College [it became The College of New Jersey in 1996]. I applied and was offered the position. Though a relatively small college, it had a very large library, with a good, engaged staff, and a director who wanted a fine academic collection. One of the job’s attractions was that it was a faculty position, with a faculty schedule, which is to say: summers off. I’d be able to write.

A few months after I started, that earliest book of mine was published. I first saw it among a load of new books that had just come into the library. Also, halfway through my first year my position was fundamentally altered. Librarians would no longer be faculty. No summers off. (See the “Story Behind the Story: Captain Grey,” for more about this event.) I stayed at Trenton State. I really loved being a librarian. But my ultimate goal was still writing, by now writing exclusively books for young people.

Over time, a great deal of my library time was devoted to teaching new students how to do research. But I was also teaching myself how to do research, and that altered not only what I wrote, but how I researched what I needed to learn to write my historical fiction.

I remained at Trenton State for sixteen years. If you happen to read my thriller, Wolf Rider, you might be interested to know it is set on the Trenton State Campus.

I remained at Trenton State for sixteen years. If you happen to read my thriller, Wolf Rider, you might be interested to know it is set on the Trenton State Campus.

By 1968 I had published eighteen books and felt a need to change things: I wanted to write full time. My goal—financially—was that I had to make at least as much as I made as a librarian. Not, as any librarian knows, the highest bar. I gave myself one year.

To be continued.

1 thought on “How I Became a Librarian, Part II”

I love reading this and learning more about you in the early years. I had no idea. Can’t wait to read more. I adore Charlotte Doyle and Sophia’s War especially. Kids are lucky. We spend a lot of time in Yardley. Thank you for being a writer.