Readers have asked me about my use of language in my historical novels, particularly words that themselves are part of the historical moment. Let it be said that, to begin with, I have a great fondness for words, and happily, the English language has an immense vocabulary. Also, I have access on my computer to the Oxford Unabridged Dictionary which has an historical thesaurus. I also own such books as Medieval Wordbook (Cosman) and Colonial American English (Lederer)

How can one resist such words as this 1774 word, mazy—winding—as in “Where the clear rivers pour their mazy tide.” Or, laverer, the medieval court servant “in charge of ceremonial hand washing with fragrant, spiced water.” One of my favorite words is the late 19th century word for sulk: pout-mouthed. That appears in my book, City of Orphans, set in that time.

How can one resist such words as this 1774 word, mazy—winding—as in “Where the clear rivers pour their mazy tide.” Or, laverer, the medieval court servant “in charge of ceremonial hand washing with fragrant, spiced water.” One of my favorite words is the late 19th century word for sulk: pout-mouthed. That appears in my book, City of Orphans, set in that time.

Similarly, if you are writing a medieval historical novel, you won’t include a steel sword, because the metal didn’t really come into use until the 16th century.

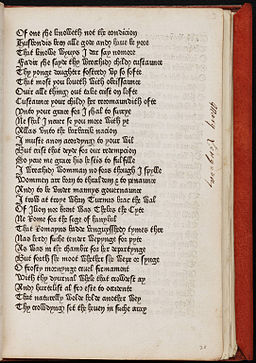

When I wrote my Newbery book, Crispin, I had another problem. The novel takes place at the end of the 14th century, when the English that was spoken was Middle English. You can get a taste of it by looking at Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, as he wrote it. When you hear it read aloud you can hear our modern English, but it is hard to recite. Need I say: I can’t write it, nor can I read it.

What did I do?

In preparation for the book I read the major English poets of the day, Chaucer, Gower, Langland. I realized they wrote their verse in iambic pentameter, “A line of verse with five metrical feet, each consisting of one short (or unstressed) syllable followed by one long (or stressed) syllable, for example Two households, both alike in dignity” which can be very close (but different) to today’s spoken English. So when I wrote Crispin I tried to write it in that verse pattern. How successful was I? I’m not even sure. But if you read the book aloud, you will (I hope) catch that rhythm, and it was, I think, enough to create, if you will, an “antique” sense of language.

Recently I was reading an historical novel (told in the first person) set in Tudor England. The author used the word “fug,” (“A thick, close, stuffy atmosphere, esp. that of a room overcrowded and with little or no ventilation.”) Liking the word’s sound, and guessing its meaning by context, but not knowing what it meant exactly, I looked it up in the OUD. I learned that the word fug wasn’t introduced into the English language until 1888.

Was it wrong to use Fug in a novel set in the 16th Century? I suppose from a purest point of view it is. But it sounded old, and it worked for me. Besides, I do think a writer is free to use any English word. You can even make them up. Shakespeare, it is claimed, invented some 1700 words, many of which we still use.

Or you could engage in Kenning: “The Anglo-Saxon and Old Germanic poetic technique of describing something without naming it, achieved by joining two or more of its major qualities; the ocean as “the whales’ road”, a high prowed sailing ship as “a foamy-necked floater”; a well-wrought sword as “Hammer leavings.”

As long as the word’s meaning is clear—not fug—I think any word you want is just fine.

2 thoughts on “Fug”

I really enjoyed the slightly ‘old’ language in Player King. It really contributed to the mood.