I spent the summer of my 16th year at a work camp run by the Society of Friends (Quakers) on a Cherokee reservation in North Carolina. There, with other teenagers, I labored with the local people, doing farm work, helping to clear wooded areas to bring in electricity, rebuilding homes, plus a great variety of useful community tasks. I also had many talks with the camp head, who provided me with an introduction to the Quaker faith, which made a strong impression on me, and about which I would subsequently read a great deal.

I spent the summer of my 16th year at a work camp run by the Society of Friends (Quakers) on a Cherokee reservation in North Carolina. There, with other teenagers, I labored with the local people, doing farm work, helping to clear wooded areas to bring in electricity, rebuilding homes, plus a great variety of useful community tasks. I also had many talks with the camp head, who provided me with an introduction to the Quaker faith, which made a strong impression on me, and about which I would subsequently read a great deal.

Years later, I was living in Lambertville, New Jersey, on the banks of the Delaware River, right across the way from Pennsylvania. My boys came to attend the Buckingham Friends elementary school, a Pennsylvania Quaker school, which had a number of quite beautiful 18th Century structures. By way of coincidence, the headmaster of the school was the same individual who ran that work camp to which I had gone.

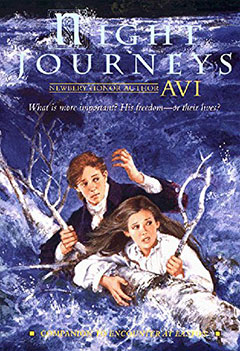

It was a combination of my interest in Pennsylvania Quakers, colonial American history, and the place where I was living, that led me to write the historical novel, Night Journeys.

The Quaker religion, like all religions, is complex and, again, like all religions, theory and practice is full of contradictions. I recall reading about the wealthy Pennsylvania Quaker farmer who, being opposed to war, refused to pay a tax levied for what we call The French and Indian War. But, not wishing to go against the law, he left the right amount of tax money on a log where the tax collector could “find” it.

It is just this kind of moral predicament which lies at the heart of Night Journeys, when Peter York, an orphan boy, is taken into the home of Everett Shinn, a deeply religious Quaker. What law (sacred or secular) should be followed when two local indentured servants run away to seek their freedom? In the book I wrote one of my favorite sentences, the one from which the title of the book derives: “Roads at night are always new.”