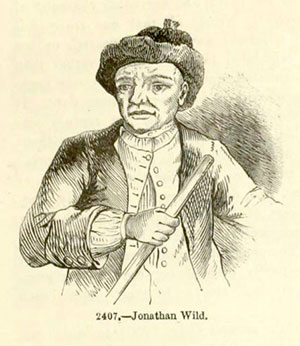

Jonathan Wild (1685–1725) was England’s most notorious crook. Daniel Defoe (Robinson Crusoe) wrote about him, as did Henry Fielding (Tom Jones). It has been suggested that Dickens’ character, Fagan, from Oliver Twist is based on him. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes’ arch rival, Moriarty, is also said to be modeled on him.

In 18th Century England, poverty was extreme, wealth was extreme, and the city of London was growing to monstrous proportions. Hardly a wonder; crime became rampant. The government enacted a series of laws to protect property, collectively known as “The Bloody Codes,” which established draconian penalties for what we might, today, consider relatively minor crimes.

Regarding criminal enforcement, England—and London—had no professional police forces. Thieves were to be apprehended by citizens, and brought to magistrates for trial. If convicted, a citizen would be rewarded by large sums of money. No surprise, professional “thief-catchers” came into being.

The greatest thief-catcher of all was Jonathan Wild—except Wild employed the thieves. The thieves would give Wild the loot, then Wild would sell the stolen property back to the victim. And/or, if the thief did not please Wild, Wild would turn the thief in, and collect a reward. Wild kept careful ledgers of his activities. If he did not like what you did, he put an X next to your name. Run afoul of him twice, a second X would be put down, and Wild would turn you in. Hence, you would have been double crossed, the origin of the word.

It was said that Wild grew immeasurably rich as he controlled most of the crime in England, Scotland and Ireland.

It was as I learned about England’s criminal world, that I created the story of Oliver Cromwell Pitts, a boy who becomes entangled in England’s criminal world and its legal system. Jonathan Wild is part of the story, and makes an appearance but, however important he is to the plot, it’s a small part. Vastly more important is the 18th Century world in which Oliver lives.

It was as I learned about England’s criminal world, that I created the story of Oliver Cromwell Pitts, a boy who becomes entangled in England’s criminal world and its legal system. Jonathan Wild is part of the story, and makes an appearance but, however important he is to the plot, it’s a small part. Vastly more important is the 18th Century world in which Oliver lives.

Indeed, part of the book’s style derives from 18th Century fiction, Fielding, Sterne, and others.

To write this way gives me—and readers—much fun, because 18th Century writing is playful, sly, satiric—and full of energy. One must be clever to write this way, clever in the sense that one never knows what will happen next. I am constructing a house of many doors—and you, the reader, never know what is behind the next door.

As for Wild, he was executed when the government double crossed him. In the curious way of English culture, Wild’s skeleton is on display at the Royal College Hunterian Museum in London.

As for The Unexpected Life of Oliver Cromwell Pitts, it’s on display at better book stores everywhere.

3 thoughts on “Story Behind the Story #66: <br>The Unexpected Life <br>of Oliver Cromwell Pitts”

Fascinating!

I agree!

I also agree. The stuff about Jonathan Wild was a revelation to me. I love knowing the origin of “double-crossed”!