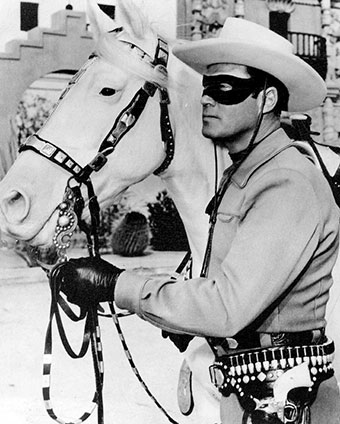

“A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust, and a hearty Hi-Yo Silver! The Lone Ranger!” (Followed by the finale of Rossini’s William Tell Overture.)

It’s difficult to explain the enormous impact radio drama—kids’ radio drama—had on me. When a boy, I listened to it every day, starting at five in the afternoon. Nights too. The Lone Ranger—one of my particular favorites—was an evening show (7:30 PM) that was listened to, apparently, by as many adults as kids.

It began broadcasting in 1933. At one point it had twenty million listeners.

[photo: public domain]

For the most part, the radio shows I listened to were very kid-related. For the Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy show, which was an afternoon crime-stopping adventure series, when a case was solved (it took a few weeks) the characters had a party, during which time they reminisced about the adventure and sang family songs, such as “My Grandfather’s Clock.” (I can still sing that song.) The party came to an end when a phone rang and it was always the Police Commissioner who would say something such as, “Jack, I need you down at headquarters right away. We’ve got a bad situation.” And off Jack—and his pals—went to solve another crime with me in tow.

And once, during Sky King, while vanquishing giants in some Central American jungle whilst searching for a lost Egyptian city (I kid you not) the giant was tied up using Sky’s side-kicks school tie, which of course he was properly wearing.

Then there was Edward R. Murrow’s You Are There which took historical events—such as the Battle of Bunker Hill, or the Wright brothers’ first flight—and “reported” them as contemporaneous news stories. “The redcoats, bayonets extended, are now advancing up Breeds Hill …”

As for the Lone Ranger, there were certain rules he had to follow. Among them, “He always used perfect grammar and precise speech devoid of slang and colloquialisms.”

These shows were elemental narratives, with a classic beginning, middle, and end construction. If one wanted an education in standard story construction, one would learn (as I did) just by listening.

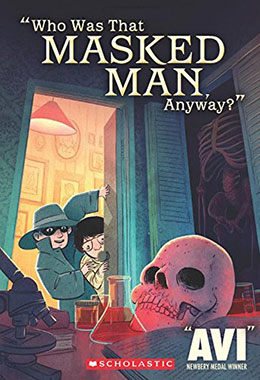

In my novel, Who Was That Masked Man, Anyway? I tried to show how radio affected my life and thoughts. It details my first efforts at story creation, as I invented and enacted adventures. It is also, I think, my funniest and most unusual book, being one-hundred percent dialogue.

When I did my due diligence for the book I listened to the old shows and was astonished at how well I recognized the actor’s voices. Sometimes I was even sure I remembered individual shows. But let it be said, the plots were so repetitious to have heard one was—in many ways—to have heard them all.

Who Was That Masked Man, Anyway? uses transcriptions of some of my favorite old shows. I included a Superman excerpt, but the copyright holders insisted it be taken out. They also insisted that we take out one of the best insider jokes, as told by protagonist Franklin D. Wattleson (known as Frankie) when he suggests that Margo Lane (the Shadow’s girlfriend) and Lois Lane (Superman’s girlfriend) must be sisters.

(And if you think I was the only one who found the name “Margo” romantic, reread Stuart Little.)

For purposes of the plot in my book, I had to invent and write one radio episode. When I was writing it I had this stunning realization: It was not novels I should have been writing, but radio adventure series!

At the end of each episode of The Lone Ranger, someone would ask, “Who was that masked man, anyway?” From a distance, you would hear, “Hi-Yo Silver, Away.”

Thrilling, to this kid.

Hey, guys! Don’t forget to tune in next time.