The book as we know it today—multiple pages bound together on one side, the pages capable of being read individually—was first called a codex and can be found in the Roman world as early as the first century (Common Era). As a form—contrasted with a scroll—it became popular in so far as it was the format most often used for the Christian Bible. (“The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel,” “The Book of the Prophet Jeremiah,” etc.) By the sixth century, it was the preeminent form of text dispersal and the primary format for reading.

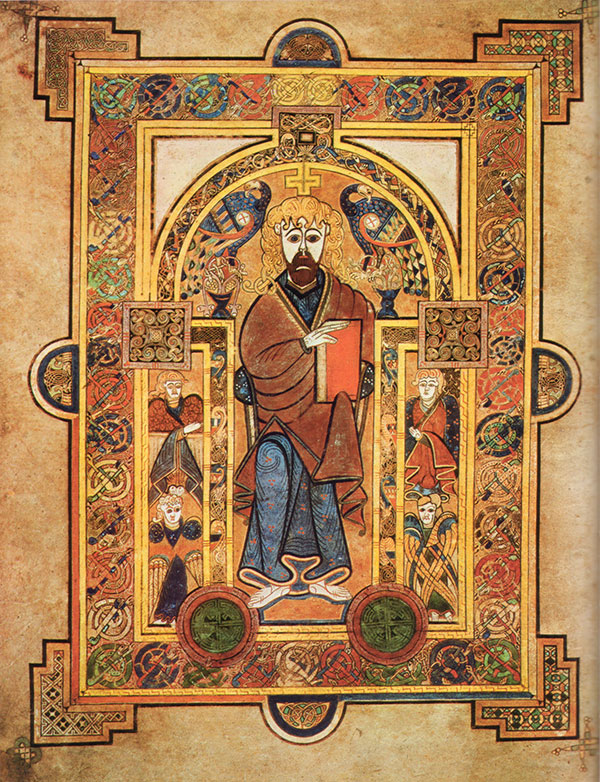

Of course, those early books, whose pages shifted from papyrus to parchment, were made, and lettered (and illustrated) by hand. Those books, such as the Irish ninth century Book of Kells, are considered great works of art.

Image in the public domain, CCBY Wikipedia.

Paper is a fifth century Chinese invention, which only comes to Europe in the fourteenth century. The first printed book using movable, exchangeable type, The Gutenberg Bible (1455) was, for the most part, printed on paper, but some were printed on vellum—a material made from animal skins.

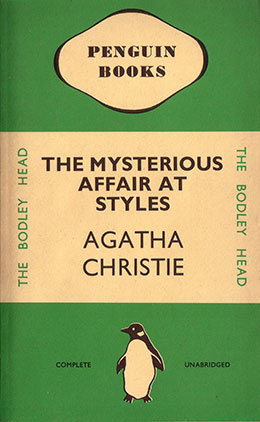

With the universal spread of printing, paper soon became the primary substance on which the printed book existed. It further evolved with the British publication of paperbacks in 1935, the “Penguin” books.

In the course of my lifetime, the printed, hard-bound book has undergone a massive transformation. It is still a codex, but the quality of the book itself, the binding, the paper, the design, and the printing has, in my mind, greatly deteriorated.

Not so long ago, upon receiving my first copy of one of my books, I felt obliged to write to the publisher to object to the quality of the book. In particular, the paper could hardly be considered white, but was, rather, a muddled gray, a gray which obscured the many fine-line illustrations and obscured the text. The paper, to the touch, was crude.

No reply from the publisher.

Consider me old-fashioned but I think there is something one can call the art of the book, the book itself as an object of beauty, a beauty which can, and should contribute to the pleasure of reading. The way a book is printed, its shape, design, the clarity of the font, the formatting, the layout on the page, the quality of the paper, the binding, the very feel of a book in my hands, all of these things are important to me as a reader, and writer. A book is more than just text. It is an experience.

And now we have electronic books. E‑readers.

Let me say I own an e‑reader. It sits bedside so that when I by chance wake in the middle of the night I can read myself to sleep without a light that might disturb my wife.

But the experience of reading electronic books, is at best, soporific. Every page of every book looks and feels the same. I might be reading a biography of Queen Victoria, or a science fiction adventure set on an exoplanet, it makes no difference. I am not on page 45, but at “13% of the text.” The illustrations are awful.

Most importantly, my mind, such as it is, slips and slides over the text, as if I were racing on an icy sidewalk. It makes for sloppy reading. I find myself forever skipping text and retaining far less of what I read.

Let me also say that in the world of young readers, the book as a thing of beauty, is of particular importance. It enhances the practice of reading insofar as a beautiful book adds to the distinctiveness of that book. Each book becomes (or should become) its own experience.

Indeed, going back to where I began, in Roman times, as the first century Cicero wrote, “A room without books is like a body without a soul.”

1 thought on “The Art of the Book”

I agree with Cicero. I have bookcases in nearly every room in my house. Sure, I could, and do, read online for information, but if I really treasure a story or poem, I like to put my hands on it.

I value your books and your blog. I always find nuggets to chew on. Thanks.