In a review of the recently published book, A Miscellany of Advice and Opinions by C. S. Lewis, the author of “The Chronicles of Narnia,” is quoted as offering this advice to would-be writers:

“1. Turn off the radio. 2. Read all the good books you can and avoid nearly all magazines. 3. Always write (and read) with the ear, not the eye. You should hear every sentence you write as if it was being read aloud or spoken. If it does not sound nice, try again.”

That was, apparently, written in 1959. Substitute “internet” for “radio,” and it’s still great advice.

It also fits nicely with what I recall (correctly, I hope) Stephen King suggesting: “You don’t know a writer until you hear him/her.”

And while I’m at it, I might as well add this advice from the 5th Century (BC) Greek philosopher, Diogenes: “We have two ears and one tongue so that we would listen more and talk less.”

My editor of many years, Richard Jackson, once told me he read (out loud) all the manuscripts he worked on. I have no doubt it contributed to his enormous success.

I am a believer that the best way to teach young people how to write (and read) is to read to them out loud. It is also—as per the above—the best way to improve your own writing.

As I have written here before, part of my writing process is to always read my work out loud. I first read the text to my wife. Then I like to read drafts to a class of students—the people for whom I am writing. When I do these readings I do so with a pen in hand. When I come to a spot that makes me wince, shake my head, or just think “that’s wrong,” I mark the page, and at the first, (quick) opportunity revise the written page.

As anyone who reads or listens to poetry knows, the choice of words, the sequence of words, the flow of words, and the sound of words matter. We sometimes forget that those sounds provide subtle (but potent) meaning.

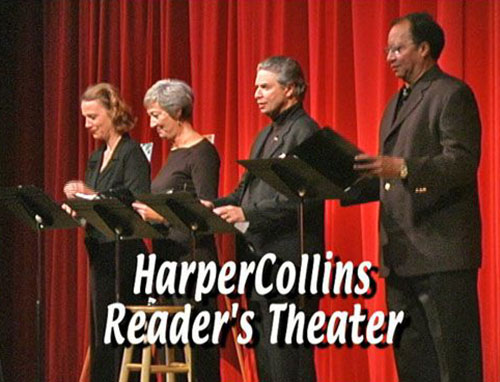

One of the most satisfying times in my writing life was when I was part of the Authors Reader’s Theatre. Working with Sharon Creech, Walter Dean Myers, and Sarah Weeks, (among others) we performed sections of our work before live audiences. The interplay between the writers, the audience, and the words was palpable and wonderfully satisfying, often moving.

Even when I was doing solo readings of my work—in a concert setting—I would learn about my work—what made it work, and what made it not work—even as I performed.

To those of you, teachers and librarians, even if you are just reading to your kids at home, I have a suggestion: take voice lessons. (I did) Learn the relatively simple techniques of speaking, pacing, breathing (as you read), articulating, plus much more.

Just the other day I was in the process of submitting a new book to my editor. I must have revised the first page a hundred times. Surely I did that for the first sentence.

Still, truly moments away from pushing the “send,” button I read out the opening line of the book yet again.

It didn’t sound quite right.

So, I changed it. For the better.