As I was working today on a book, a message suddenly popped up on my screen:

“Did you know that you used more unique words than 85% of Grammarly users?”

First, I was startled by the apparent fact that Grammarly was tracking my words. Secondly, I wondered why they were tracking my work. Thirdly, while I am aware that I have a large vocabulary, and that I try to make my writing varied, I make it a point — considering my young readers — NOT to use obscure or excessively complex language. In fact, I am a believer in simple, straightforward writing to express the emotions about which I am writing.

On the same day, I read an article in the New York Times, “An Ancient Solution to Our Current Crisis of Disconnection.”

The article, by Mr. John Bowe, had this to say:

“Hannah Hobson, a lecturer in psychology at the University of York [UK] who has studied the connections among language, communication, and mental health … has found repeatedly that the inability to express feelings or ask for help can often correlate with existing or developing mental health issues among youth. Conversely … improved communication skills correlate with youngsters’ emotional development and well-being.”

Mr. Bowe is proposing the teaching of the (now) ancient teaching of rhetoric, which in its simplest form is the art of speaking and listening. When you consider the brevity of e‑mail, the general decline in reading, and that social media communication is as slight in form as it is in content, it is hardly a wonder that young people have not been taught how to communicate their complex feelings and emotions.

One often hears the general sense that young people, in particular adolescents, are very emotional. True enough. And yet, in our current society, their experience with how to express those emotions is at best limited, cut off, and truncated. That inability to communicate apparently can lead to mental issues.

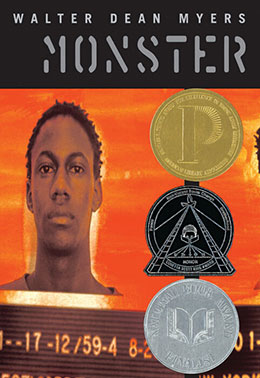

A good number of years ago I was asked to speak at a boy’s juvenile detention center in Virginia. Slumped in their chairs, their body language telling me that they were forced to be there, the young men were polite, but clearly not particularly interested in what I had to say or me for that matter. That is, not until it came out that Walter Dean Myers was a good friend of mine. Then they literarily sat up in the chairs and began to pepper me with questions about him. It appeared that many of these young prisoners had read Monster, and the book had articulated their feelings, so that I, by virtue of my connection with Walter, was suddenly given a flood of words and ideas. It was startling and powerful evidence of what a book can mean to young people.

I don’t want to suggest that reading is a cure for all the problems of mental illness in our country. But I will say if people cannot be taught or experience how to express their feelings, frustrations, and conflicts with words, they will find ways—destructive ways—to express their emotions.

Social media is often (rightly, I think) criticized for its misinformation, lack of real content, and simplistic articulation, but perhaps its most profound problem is that it is an inept way to communicate.

So, when I am told (by Grammarly) that my writing is full of unique words, Grammarly is not so much praising me, as revealing that a large part of the population is inarticulate.

The moral: be worried about the person who cannot speak or write their thoughts.