Hilary Mantel, the late British author who wrote such outstanding historical fiction as the Wolf Hall trilogy, is quoted as saying, “History is not the past, it’s the method we have evolved of organizing our ignorance of the past.”

That’s also an apt definition for historical fiction, as it is the academic discipline of history itself. The difference; the historian, at least we like to assume, is trained to search out the facts, data, and other evidence to present a meaningful — and objective — narrative of past events.

The writer of historical fiction, while trying to hew to selective facts, invents a personalized accounting for what happened. It suggests real history even though it isn’t. It’s also subjective in its point of view.

Historical fiction — which, in English, seems to have begun with Sir Walter Scott’s Waverly published in 1814 — takes many forms. Its authors follow facts in varying degrees. Thus, my The Button War is based on a brief story my late father-in-law told me about his experience in World War One when he was a boy. Otherwise, it is utterly fiction.

Gold Rush Girl, set in 1848 San Francisco, is as close a factual rendering of Gold Rush San Francisco as I could create, based on my research. Early in the book, the girl protagonist attends a dance class on the East Coast. I tracked down a mid-19th-century etiquette book that had rules for such events. You may be sure I used it. That said, the story in Gold Rush Girl is entirely invented.

In my recent Loyalty, a tale of the early days of the American Revolution, I could take advantage of the many accounts of the battles of Lexington and Concord. But in my telling, I inserted a fictional character who reacts to the battles in a very personal way: he is a witness not just to the battles, but to the death of his brother-in-law.

The story I tell is fiction, but, besides the details of the battle — which I believe are true — I have my protagonist — witness that death. Fiction. But I gave that brother-in-law the real name of a young man who actually died in those battles.

Fact and fiction combined.

Sometimes I am corrected. In The Secret School, set in 1925, fourteen-year-old Ida drives to school in a Model T Ford. (Colorado introduced driving licenses in 1936.) She handles the steering wheel. Being very short, her younger brother Felix, on the car floor, works the brake and clutch pedals. Those peddles, as I researched them, were many and complicated to use. In my telling I got the pedals mixed up. Shortly after publication, I received a letter setting me to rights. Later editions have those pedals right.

Now, in 2024 I will be publishing (working title) Lost in the Empire City. Set in New York City in 1911, it tells the tale of an immigrant Italian boy who must navigate the most crowded city in the world — on his own.

There are countless accounts of immigrants passing through Ellis Island. They are fascinating, and often moving. As it happens, one of the accounts I read was by my grandmother, Miriam Shomer Zunser.

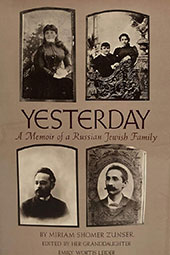

Her memoir, titled Yesterday, was first published in 1939, then edited by my twin sister, Emily Leider, and reissued by HarperCollins in 1978. It recounts among many other things, how, as a girl, my grandmother came to America from Ukraine in 1889.

In the book, my Grandmother recounts how, when she arrived in America, she was given a banana by her father. Never having seen a banana before she was greatly puzzled as to how to eat it.

That factual incident is in my fictional book.

A 19th-century fact, written down by my grandmother in 1939, edited by my twin sister in 1978, written into my fiction in 2024.

My way of organizing the past into a contemporary fictional narrative.