In 1835, Charles Dickens, aged 24, was a working UK Parliament reporter and freelance reporter, when the English publisher Chapman & Hall began to issue a series of illustrations — “Cockney Sporting Plates” by artist Robert Seymour. Dickens was engaged to provide written commentary for the art. But after two art episodes, Seymour died. Dickens, however, was asked to continue the narrative and thus created The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, which was serialized (each installment “to be continued”) from March 1836 to November 1837.

The Pickwick Papers — as it became known — became a literary sensation, launched Dickens as a major writer, and established serial fiction as a literary staple that became enormously popular, used by many writers and publishers.

At the time — the 19th century — mass literacy was rapidly expanding, printing was becoming more efficient, and serial novelization made the cost of book reading much lower for the general public. Moreover, it transformed reading from an individual endeavor to a social phenomenon, with huge numbers able to simultaneously share a text.

Was serialization popular? Consider this abbreviated list of literary staples, all of which are now considered literary classics, all of which were serialized.

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (1844)

- Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray (1847)

- Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1851)

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1856)

- The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins (1859)

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866)

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne (1870)

- Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871)

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1875)

- The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James (1880)

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson (1881)

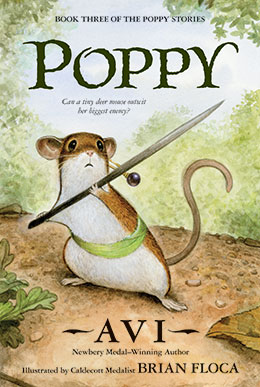

When I was a boy, growing up in New York City, my parents’ daily newspaper of choice was the NY Times, which, aside from its sports pages, I found dull. But occasionally into the house came The New York Herald Tribune, which not only had daily comic strips, but ran serialized animal stories by the American author Thornton W. Burgess. I adored those stories (Blackie the Crow, Lightfoot the Deer) and reading them led me to the local used bookstore where I would buy volumes of the complete stories, for twenty-five cents each. Those stories taught me to become a lifelong reader. Understandably, I never forgot the enormous pleasure those serial stories gave me. And I have no doubt they influenced my Poppy books.

In 1995, when visiting schools, I noticed that middle school readers were enjoying long novels (e.g., Stephen King) on their own, far outside of school curriculums. I set out to write such a long book using as my model the great Victorian serialized novels, such as above. My Beyond the Western Sea was the result. An adventure tale (of 675 pages), it featured short, cliff-hanging chapters of a hopefully engrossing story. It worked. Readers asked for more!

In 1996, while living in Boulder, Colorado, with access to a small-town newspaper, I wondered if I could take the next step and write a serialized story that could be published, chapter by chapter, in the local press. Keep Your Eye on Amanda, illustrated by Janet Stevens, was the result. And that in turn led to the creation of an enormously successful publishing venture, Breakfast Serials.

Here is a link to Breakfast Serials on Substack: breakfastserialsinc.substack.com

This story of Breakfast Serials to be continued next week …

1 thought on “Serialization, Breakfast Serials, and Substack”

Avi, I really like the Poppy series. I think I have just about every book in the series. I am not a kid anymore but I still liked these books. Did you read that they’re training otters and rats for search and find? That would make a great story too.