We are approaching the celebration of 250 years of American Independence. Hurrah, but …

I suspect that every country has stories about its national origin. I also suspect that such stories — often about revolutions — are a mix of historical facts, historical courage, and mythology. The mythology is often used to smooth out the rough edges of what must have been messy, multifaceted, and often violent times. Some facts are hidden, forgotten, or even denied. Other facts are exaggerated. Sometimes events are invented. I’m a believer that history is never simple, but complex, and therefore endlessly fascinating.

Consider “The shot heard around the world.” The phrase refers to the first shot fired at the April 19, 1775, battles of Lexington and Concord, which in traditional historical accounts mark the beginning of our War of Independence. The phrase comes from a poem, Concord Hymn, written by Ralph Waldo Emerson, published more than fifty years after the event.

The historical evidence suggests that indeed such a shot was fired, and the reaction to it did bring on the battles — and the war.

But who fired that shot? Was it an American? Was it a British Soldier? Was it someone standing on the sidelines? Might it have been just an accident?

The historical evidence provides no clear answer. It could have been any one of these conjectures. Certainly, no one took credit for it. Indeed, each side accused the other of that first firing.

But it did happen.

As the writer Paula Fox once said to me, “The writer’s job is to imagine the truth.” So when I wrote Loyalty, my novel about the early days of the war, and came to describe Lexington and Concord, I tried to keep that ambiguity. Complexity seems closer to the truth about humans, rather than larger-than-life pure heroes.

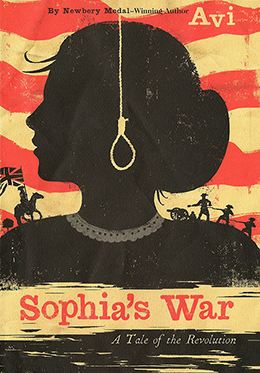

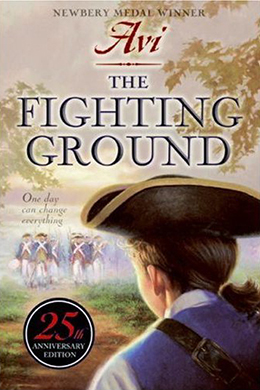

I’ve written about the Revolution in a number of novels. They include Loyalty, Sophia’s War, and The Fighting Ground, to put them in historical (not publishing) chronology. In all of these books, I tried to explore the intricacy of the long conflict, not just to repeat easy mythology.

In the Fighting Ground, my young protagonist is captured by Hessian troops. Mercenaries, they speak their native German, but Jonathan thinks he knows what they are saying. In the book’s afterword, the German is translated, and it is not at all what the boy thought. That afterword rewrites the book. Afterwords often do.

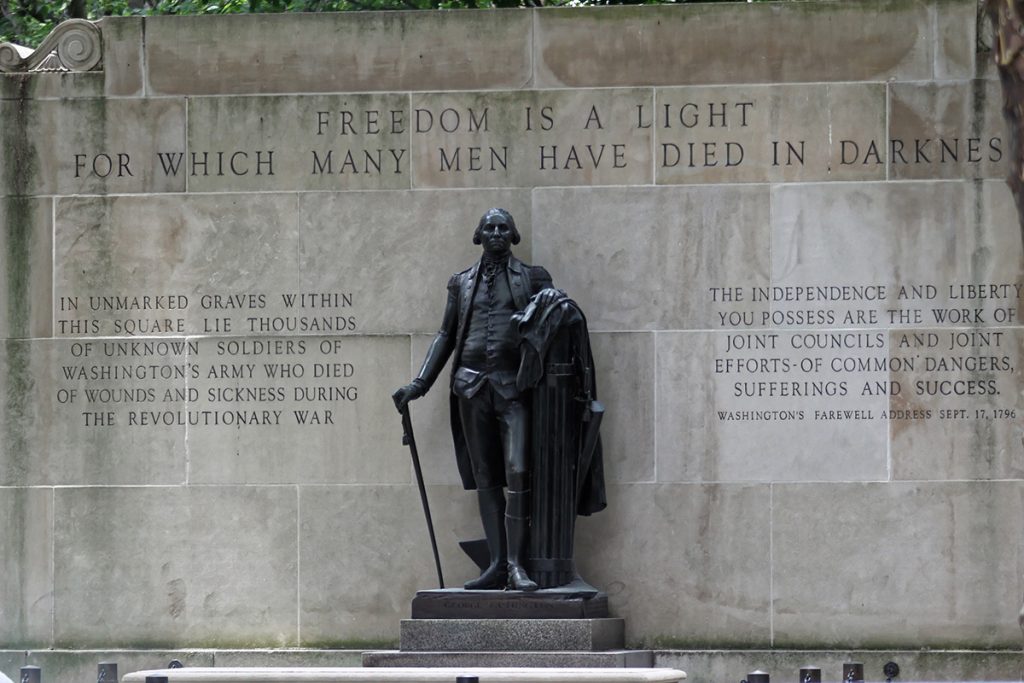

I am not sure when I became interested in the American Revolution. I was raised in Brooklyn Heights (NYC), which was the site of one of the major battles of the war and came to be called the Battle of Long Island. The land under the house I lived in was probably trodden on by the engaged armies. Then, too, as an adolescent and a voracious reader, I somehow latched on to the American writer Kenneth Roberts, who wrote big, complex historical novels about the Revolution. They fascinated me. In one of them — Rabble in Arms (1933) he introduced me to Benedict Arnold, who would appear in my Sophia’s War, where I created a story — sticking to the known facts — as to how he was caught out as a traitor.

I am not sure when I became interested in the American Revolution. I was raised in Brooklyn Heights (NYC), which was the site of one of the major battles of the war and came to be called the Battle of Long Island. The land under the house I lived in was probably trodden on by the engaged armies. Then, too, as an adolescent and a voracious reader, I somehow latched on to the American writer Kenneth Roberts, who wrote big, complex historical novels about the Revolution. They fascinated me. In one of them — Rabble in Arms (1933) he introduced me to Benedict Arnold, who would appear in my Sophia’s War, where I created a story — sticking to the known facts — as to how he was caught out as a traitor.

My first published piece of writing was a play about Nathan Hale, the young teacher who is reputed — just before he was hanged by the British as a spy — to have said, “I regret that I have only one life to give to my country.”

Did he say that? Maybe.

I continue to read about the Revolution and all its complications. One interesting example: Benjamin Franklin, whose support of the Revolution was of fundamental importance in moving to independence, winning the war, and gaining the peace, had a son who was a loyalist, a man who helped raise troops to fight with the British, against independence.

Then there is “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” That beautiful, stirring statement was written by a man who owned enslaved people.

(Read Scars of Independence [Holger Hoock, 2017], which recounts the Revolution as much as a civil war as it was a war for independence.)

(Read Scars of Independence [Holger Hoock, 2017], which recounts the Revolution as much as a civil war as it was a war for independence.)

I stand with those who believe complexity and contradiction are the stuff of human experience and that simplicity only hides the truth in all its richness.

The American Revolution is full of that richness, full of fascinating, real, complex humanity. I hope we celebrate that, too.

1 thought on “Tales of the American Revolution”

Excellent commentary on, as you say, the complexity inherent in the reality of seemingly simple yet historically significant events. I love how your novels weave the big and small, the major and minor characters, and the fiction and non-fiction masterfully together!