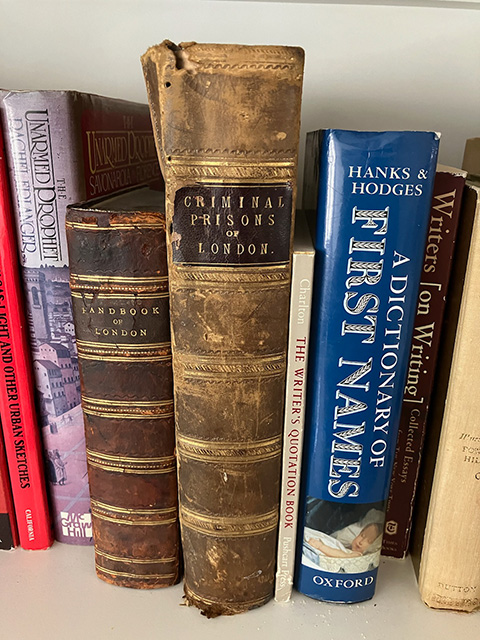

I have a fondness for old books. The oldest on my shelf was published in 1850 and has the title, Handbook of London, Past and Present. I believe I acquired it when writing Traitor’s Gate. It was wonderfully useful when trying to track the streets and places in London at that time. The other very old book I have on my shelves is Henry Mayhew’s Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of Prison Life. It is dated MDCCCLXII (1862). This volume is splendidly illustrated. Here again, I believe I used it while researching Traitor’s Gate. There are scenes in this old book that provide extraordinary details of life in an English prison. Those details became an important part of my book.

Thus, information such as the “Daily Diet list” at the House of Detention, Clerkenwell: On Sundays, Males and Females there were fed “4 ounces of meat, 2 ounces of gruel and 16 ounces of bread.” Furthermore, “All prisoners are allowed to be visited by their friends, from 12 till 2 daily, Sunday’s excepted.”

The subtext of this information is that many working people only had Sundays off, which meant they could make no prison visits to family or friends on that day.

As I am sure you can imagine, this kind of detail is invaluable when writing about such times and places.

When I hold such old books, I have to wonder who else held them, and under what circumstances. And how did they even read them? Or use them? The typeface is extraordinarily small (by today’s standards). Even more bewildering is to contemplate how the type was set and proofread.

The old leather bindings have a singular musty smell of which I’m fond. Though the paper is old, it is in better condition than many recently published paperback books. I suspect it has a high rag content.

A recently acquired book that was published in 1927 (for a current project) has on the back of the title page, a note: “Five hundred copies of this volume have been printed from type and the type distributed.” In other words, only 500 copies ever existed. I now have one of them.

In this context, I have several dictionaries, such as one of medieval words, and a reprint of Grose’s (1785) A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. (“Vulgar” here, means slang.) Thus a “filching mort” is “a woman thief.” Somewhere I have an edition of Roget’s original (1851) Thesaurus.

When doing research for The Secret Sisters — in which Ida goes to a 1925 high school, I got a hold of some textbooks from that time.

Why else would I now have a 1923 Latin textbook?

Yes, such old books provide details, but most of all they enable me to give life to my characters, situations, and even places. My readers tell me they love these details.

The truth is, so do I.

3 thoughts on “Details, Details”

Traveling and reading Avi’s blog. What could be better? Old books? 😊

Years ago, when I was dreaming up what became my first book, MAY B., a friend and I were in an antique store together. She found an old school primer from the late 1800s and handed it to me, saying maybe it would be helpful with the book idea I had. I took it home and decided it would play a role in my manuscript. It ended up being central to May’s story.

Hello, Avi, I love all of your work. My mom and I were talking and the reason your books are so good is because of all of your details, we decided. I would really like it if you created another Crispin bok, maybe you could make it when he was older? I am also hoping of becoming a great writer like you. I would love it if you could reply.

‑Philip N.