A recent article in the New York Times, “The Dangerous Decline of the Historical Profession,” by Daniel Bessner, referencing the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, reports on the massive falling off of the study of history, the teaching of history, and, inevitably, the decline in the learning of history.

A recent article in the New York Times, “The Dangerous Decline of the Historical Profession,” by Daniel Bessner, referencing the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, reports on the massive falling off of the study of history, the teaching of history, and, inevitably, the decline in the learning of history.

If you are following the national news to any extent, you are aware of the politicization of teaching history in schools.

It made me recall what George Orwell said: “the most effective way to destroy [a] people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

When I was ten years old—or thereabouts—there came into my home The American Past: a History of the United States from Concord to Hiroshima, 1775–1945. Written by Roger Butterfield, and published in 1947, it was an illustrated history of the nation, the illustrations—a massive collection of images, prints, etchings, paintings, photographs, and even (to my delight) political cartoons—all contemporaneous from the time being covered.

The book fascinated me so I went through it countless times. It was so important to me that I still have that same volume—seventy-six years old!—on my shelves.

It was through that book that I became interested in history. Because of the vividness of the illustrations, and the unfolding stories that were there, page after page, my imagination was caught. Indeed, I came to see history as story. No surprise, it was not too long before I began to read historical fiction, with Stevenson’s Treasure Island providing an indelible influence that stays with me today. At some point, I began to read a lot of adult historical fiction, in particular the work of Kenneth Roberts. There were plenty of others. I still read it.

So, it is no accident that I write historical fiction. The genre came into the world of English Literature with the publication of Sir Walter Scott’s novel Waverly in 1814. The genre quickly became (and still is) widely popular. When I went to college, wanting to be a playwright, I had a double major, Theatre and History. Surprise! My first published work was a play about Nathan Hale, that early American patriot, and martyr.

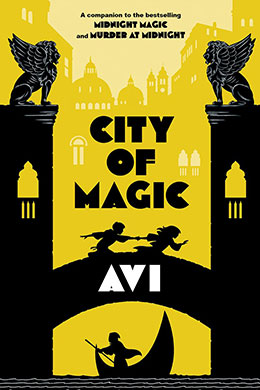

Whereas Waverly was about a major event in British history, my own offerings take a different tack. Books like The Fighting Ground, The Button War, City of Magic, The Player King, and Gold Rush Girl, among many others, deal with small (if real) events from the past. The incidents that fascinate me are the ones that show up in footnotes, not in massive monuments. How else can one discover, as I recently did, that there is a town in Colorado named “Tin Cup.” It still exists.

I don’t think of myself as (nor do I wish to be) a teacher of history, so much as I offer my books as stories that give life to the past, filling history with a living reality and humanity—not prettified but attempting to connect young readers with the real world from which they emerged.

As Michael Crichton has written: “If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.”

Another way of saying this is that, by definition, unless a person has a past, they cannot have a future.

Historical fiction is one way of providing that past.